BIG Intelligence Report Series

This article is part of the BIG Intelligence Reports Series. For more information about this article or if you have any comments, questions or suggestions for this series, please send us a note support@BIGhealthcare.ca.

Share this Report

Additional Intelligence Reports

Exclusive BIG Intelligence Data

Direct link to graphs: COVID-19 Impact on Overtime by Department

BIG Data last updated fiscal 2020/21

Introduction

BIG Healthcare collates financial and operational data from Canadian hospitals and delivers unique indicators to help hospitals assess their performance against peers and to determine optimal staffing workload.

With the aid of BIG Healthcare’s data, hospitals can assess overtime levels relative to peers and mitigate the risk of front-line burnout.

The following Ontario hospital data gives a real-life view of the current state of the healthcare system in Ontario and how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted healthcare personnel. Inferences can be made by other hospitals in Canada and allow stakeholders to devise systemic solutions using these data.

Information collected over the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic indicates a rise in overtime across hospitals compared to data from the same hospitals before the pandemic. This suggests that more health workers have had to stay at work for longer because of a surge in COVID-19 cases and hospitalization, or because of a shortage of available workers.

This is concerning because these data suggest a reduction in available manpower to cope with the large influx of patients due to the ongoing pandemic as well as hospitals resuming their regular operating schedules. This creates a sequence of harsher working conditions, low motivation, burnout and a further decrease in the number of health workers who can productively contribute to the system.

These changes in overtime show varying patterns across the different hospital types.

Teaching and larger community hospitals typically have greater access to staffing levels and replacement staff than smaller or remote hospitals. So, they can better cope with the surge in workload; though due to the decline in working conditions, the number of available staff is starting to make a significant impact.

In contrast, the situation in smaller hospitals is really at an edge. Dr. Paul Parks, who works at the Medicine Hat Regional Hospital, described the situation of medical staff as “moral distress”. “You’re overworked, have more patients than usual, and have been working for two and a half years, ” he said.

COVID-19 Impact on Overtime by Department

As part of its BIG Intelligence Report Series, BIG Healthcare produced the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Hospital Operations report that illustrated how overtime and sick time varied by hospital departments which were impacted differently by the admission of high-acuity COVID-19 patients. The following is a summary of the findings in different hospital departments.

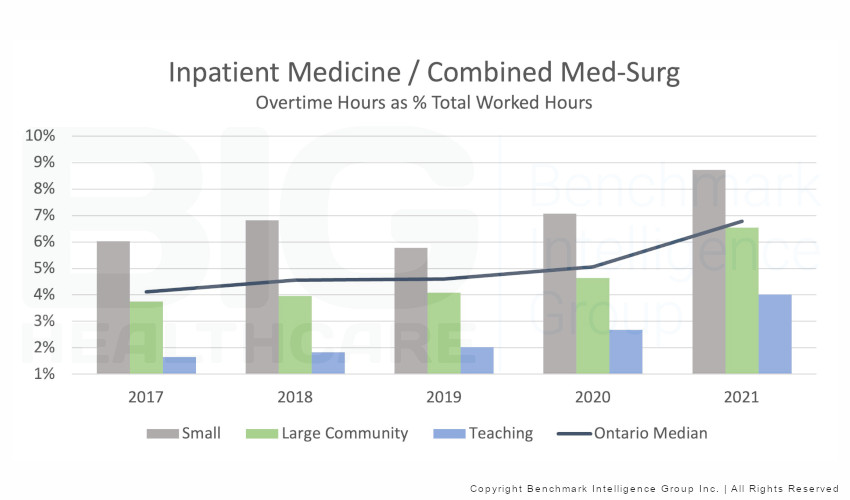

Medicine Inpatient

Overtime hours in medicine units increased by 47% since pre-pandemic levels. Teaching hospitals have experienced a near doubling in overtime since pre-pandemic levels.

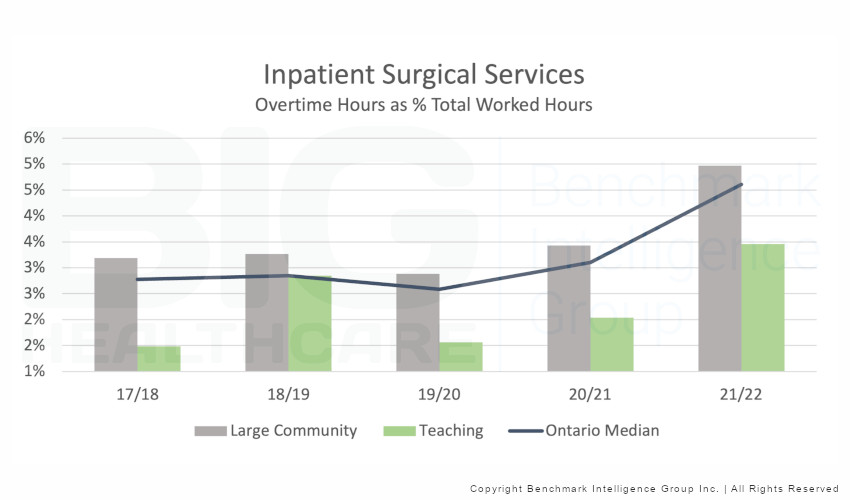

Surgical Inpatient

Overtime hours in surgical units increased by 78% overall. Teaching hospitals faced the most significant impact at 121%.

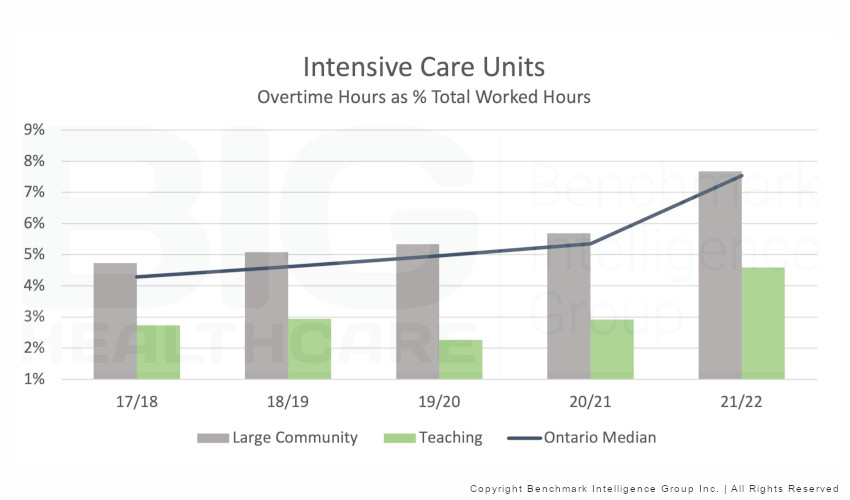

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

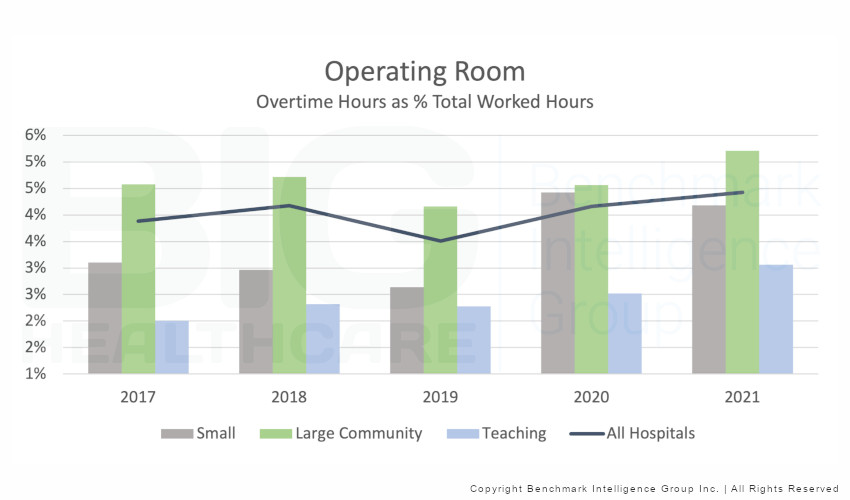

Operating Room (OR)

Overtime has experienced a steady increase since prior to the pandemic.There has been a 26% increase in the median of overtime hours across all hospital types.

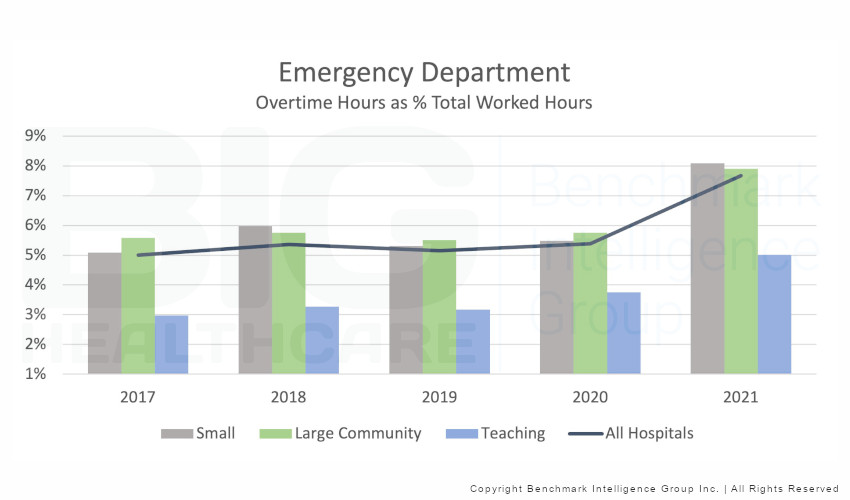

Emergency Departments

Canadian Healthcare Struggles

The persistence of the COVID-19 pandemic has taken a heavy toll on health systems globally. “Burnout” is being reported among healthcare workers, indeed front-line health personnel, due to the cycle of understaffing and harsh working circumstances caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is particularly true for Canadian hospitals. As provinces contend with the pandemic’s next wave, healthcare organizations across the country are warning that Canada’s healthcare system is “on life support“. Healthcare employees face significant system backlogs, a scarcity of colleagues to cope with demands and extreme weariness from working through COVID-19 for nearly three years.

This was corroborated by a survey of four thousand medical doctors conducted by the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) in late 2021, which found that 53% had experienced “high levels” of burnout, compared to only 30% four years prior.

Accessibility and Quality of Care

On top of that, many medical doctors, nurses, and allied health staff call in sick, raising worries about the accessibility and quality of care for patients. Despite statements from government officials, such as Premier Doug Ford and Health Minister Christine Elliot, that the provinces across the country are prepared to deal with the surge in demand, Dr. Gerald Evans, an infectious disease specialist at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, in this article says hospitals across the provinces are struggling to keep up with demand.

“Even if the number of people admitted to hospitals remains below what we saw during the fifth or sixth wave, or even if it rises to the level of previous waves, the problem is that there are significantly fewer people available to care for those people admitted to hospitals.”

Dr. Katharine Smart, President of the Canadian Medical Association, was quoted in this CMA article,

“While governments and Canadians hope to move on from the pandemic, an exhausted and depleted healthcare workforce is battling to deliver timely, required care to patients and work through a substantial backlog of testing, surgeries, and routine care.

What we heard was depressing, with health workers expressing their discontent, enduring harassment, and abandoning their jobs. We will never be able to provide concrete remedies until the government begins to recognize these issues.”

In the same CMA article, Michael Villeneuve explained how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the health workforce negatively.

“However, employees at all career phases, as well as all key sectors of health care, are now implicated, and it is apparent that health workers are on the verge of collapsing with little left to give.”

Next Steps and Conclusions

Burnout among health workers is on the rise. Earlier this year, the U.S. Surgeon General released an advisory on addressing health worker burnout, calling for increased attention to organizational and policy changes that address burnout. If healthcare capacity and staff are strained further, not only is there further risk of burnout in the near term, but it may also be challenging to recruit and retain personnel in the long run.

A recent survey conducted by Statistics Canada indicates that nearly one in four nurses intended to leave or change their job in the next three years. A similar study conducted by the American Medical Association found that one in five physicians intends to leave their current practice within two years.

It is even more important now that stakeholders and health organizations ensure adequate staffing of all hospitals through ongoing evaluation of workload and staff availability. Furthermore, efforts should be made to reduce overtime and long shifts among health personnel to mitigate burnout in the reality of ongoing pandemic